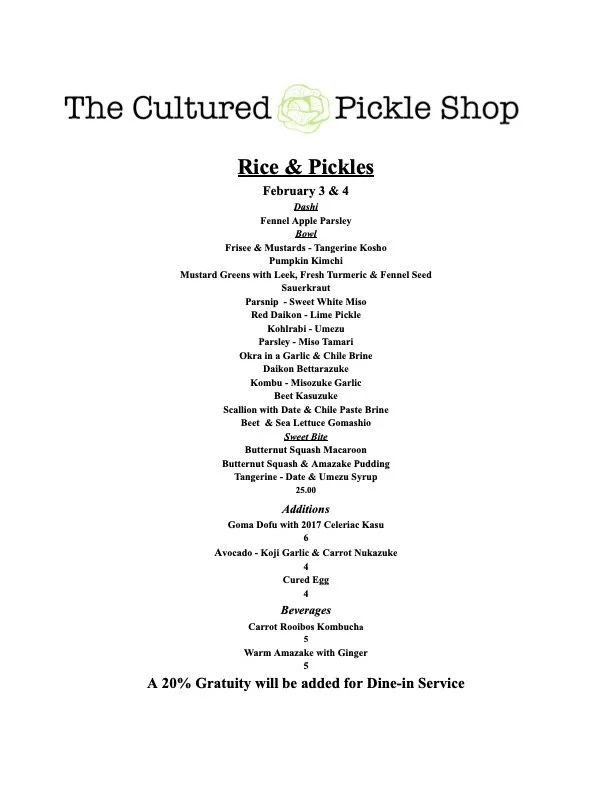

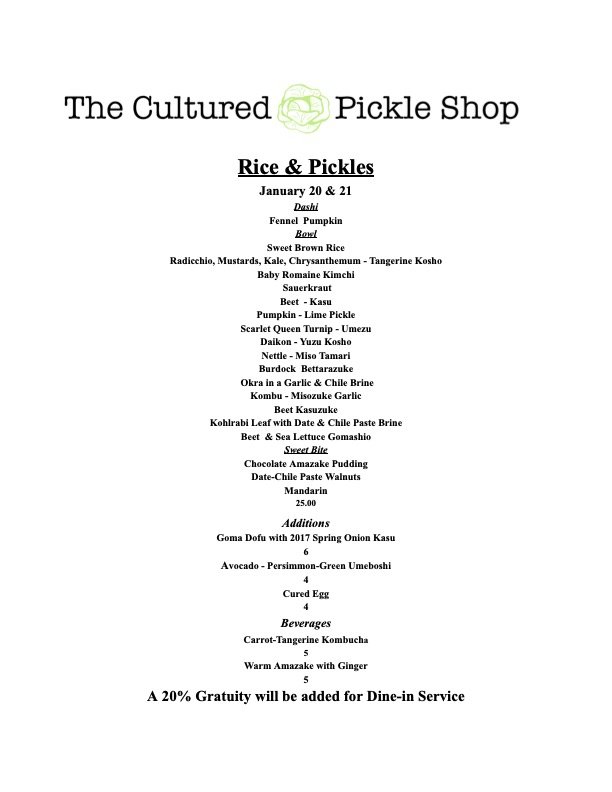

Rice & Pickles February 10 & 11

A new feature this week. You can click on the dots on each component in the bowl and get a quick description. You can scroll down for a little more detail.

Menu

We always begin the bowl with a 50/50 blend of short-grain brown and sweet brown rice, sticky or glutinous brown rice, grown by the Lundberg Family here in California. We cook our rice in a Donabe. Donabe are a family of Japanese clay cooking vessels. The Donabe we use is called a Kamado-san and is specifically designed as a rice cooker. Our Donabe comes from Iga, Japan, and has been made by the Nagatani-en family for 5 generations. Iga is a great location for Donabe making because the clay body that is found in and around Iga has a high microscopic fossil content, which results in superior heat retention in the clay products that come out of the area; so, not only is the Donabe a beautiful and effective rice cooker but it also acts a warmer as it's very slow to cool once it has come off of the flame.

We top the rice with a gomashio or sesame salt. Our take on this traditional Japanese toasted sesame and salt condiment is that instead of using salt, we use either one of our ferments that we have dried and powdered or a seaweed. Today, we have toasted sesame seeds and dried and powdered beet pulp left over from juicing beets for kombucha, which gives it color, and we use Sea Lettuce instead of salt.

Butternut Squash, steamed, pureed and seasoned with 2022 Kabocha Kasu. Takara Sake, one of the larger sake producers in our region, is just a few blocks from The Shop. We essentially tap into their waste stream; we get the byproduct from their fermentation, a paste made up of rice, rice koji, and yeast. We take that paste, called kasu or sake kasu, and we add sugar to it to feed the yeast that is still living in it; we add salt to it to moderate the fermentation and for texture preservation, and then we bury vegetables, such as Kabocha Squash, in it for an average of 12-18 months to make the pickle known as kasuzuke which means pickled in kasu. When the kasuzuke is jarred and sold we hold on to the remaining kasu for aging. We have a whole archive of variously aged and flavored kasu going back to 2011. We use it like you would use miso; as a seasoning, as a condiment, to create a broth. Here the squash puree was seasoned with kasu from a 2022 Kabocha ferment.

Romanesco mixed this week with our Indian Pickled Limes - an 11-month fermentation of limes; they are our version of an Indian achar, like the mango pickle you might get on the side of your dosa. The limes are minced, mixed with the Romanesco, and left to sit for a few days

The Nettles were blanched, shocked, and marinated in Miso Tamari, the liquid that rises to the top of the vessel during our sweet white miso production.