Mendocino County, California. Just north of Laytonville, an eye blink of a town, a loose gravel road rises up off of Highway 101 onto a hillside and disappears into a cluster of Tan Oak. Rising up almost a thousand feet, Bell Springs Road plateaus onto a ridge that provides breathtaking views of valleys containing no small percentage of the marijuana grown in the United States.There is barely a house to be seen. But dotted along the main road are gravel tributaries winding, behind locked gates, down the slopes and into the canopy of trees creeping up from the valley bottoms. Remote, it seems an unlikely place to find a farm, or at least a farm that sells vegetables. But if you look down from the ridge you’ll see it there. B and B Organic Farm, five cultivated acres carved out from a clear cut hillside.

Alex and I met on the farm in the fall of '94, and had, at this point, spent almost two years there, off and on, learning absolutely nothing about farming. Just outside the farm gates, three trailers are situated amongst some enormous oaks with giant globes of mistletoe hanging pendulously on sturdy branches. Small units, the trailers themselves serve mostly as the kitchen and dining area while a small wooden addition contains a sleeping loft and a living room heated by a wood-burning stove. It's early December, 6:30am and it’s cold. It snowed the night before and the ground is covered with a light white dusting. I poke my head up from under the blankets and watch my breath explode into steam before ducking back under. "Holy shit, it snowed," I say to Alex, half expecting her to completely freak out. After all this is California. From my Midwestern point of view, I don't associate snow with California. She gasps and says, "How cold is it?" There is no insulation in the trailer and the fire in the stove burnt out hours ago. It’s as cold inside as it is outside, in the snow. "Shit," she says, and sits up quickly pulling the blankets from me. The cold hits my body like jumping into an icy lake. "Shit," she says, "You better check on the koji!"

Koji is the Japanese name for rice which has been inoculated with a particular mold, Aspergilllus oryzae. According to William Shurtleff in The Book of Miso, up until World War II, when a pair of huge bombs upset the balance of Japans microbial terrior, koji makers would capture the wild aspergillus spores they used in koji production with huge butterfly nets. There are now very few distributors of aspergillus spores in Japan and only one, GEM Cultures, in the United States.

Koji, which in Japanese means “barley chrysanthemum,” is the agent used to create some of Japan's staple foods. Primarily it is used to ferment Miso, Shoyu (soy sauce), and Sake.

In Miso making, the inoculated rice is added to a soybean mash, then mixed with salt and left to ferment from months to years, producing a rich aromatic paste used as a soup base and as a seasoning in countless Japanese dishes. Shoyu, the ubiquitous soy sauce, is made in much the same way, only with a more liquid mash. For Sake, the mold acts in concert with added yeast to consume the starches of cooked rice, converting them to sugars and in turn converting the sugars to alcohol.

The previous week we had driven out to the coast to the town of Fort Bragg to visit the home of Betty and Gordon who started a company called Gem Cultures in 1980. If the couple were surprised to find two dirty and disheveled youngsters show up at their front door seeking obscure mold spore strains, they did not show it. They warmly invited us into their home showing us their inventory of dairy cultures and sourdough starters and packets of mold spores. We toured the gardens and stayed for lunch. We left with a new set of eyes.

Two days later, on a sunny morning that promised a warm day, we steamed a pot of Sushi Rice. When it was tender, we spread it out on a square of cheesecloth and monitored its temperature, trying to maintain some sort of standard of sterility in a barn which saw the constant comings and goings of unwashed farm workers. Taking a break from the fields and coming in for a cup of coffee or to make a quick sandwich for lunch, they would bring with them layers of tomato resin and boots coated with dirt of all sorts, mud and dust and chicken shit. We watch as the temperature falls. At around a hundred degrees, we bring out a bag in which we have mixed rice flour—toasted in a black iron skillet to sterilize it—and one packet of the powder green spores of Aspergillus mold and we sprinkle the mixture over the steamed rice. We work it through the rice making sure that each grain is coated as best we can. This process has to be done quickly; we don’t want the temperature to get to low. If it does we may not be able to bring it back up to the necessary 77-84 degrees that the spores need to take hold. Once the process is done, we mound the rice back up on the cheese cloth and, pulling the corners together, wrap it up tight. Then we bundle it in towels and place it into a down sleeping bag with several pink hot water bottles. We move the whole pile out onto the sunny hillside and go back to work.

The tricky part about making koji miles off the grid as the season is becoming cold, is not, as it turns out, keeping it warm.

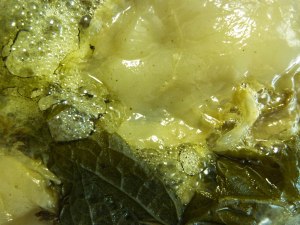

"You better go down and check on it," Alex says. I scramble out from the body-warmed blankets and lower my naked self down the ladder to the hard cold floor and over to a small, shallow wooden box lying on the ground in front of the stove. I am quite convinced that the contents will be as dead as the fire which failed to warm it throughout the night. As I put my hands on the lid to remove it and confirm my suspicions, fears of another failed experiment assail me. I curse the cold and lament a day ahead of harvesting parsley under the snow, and I notice that the lid is warm! Lifting it off and peeling back the cheese cloth, a layer of soft, white, fuzzy rice is revealed, and the thermometer is reading a staggering 120 degrees. Hot enough to burn the whole thing out. Quickly, I go into the kitchen and grab a wooden salad tong, using it to break up chunks of rice where the mycelia, looking like tiny, tight spiders webs, has bound the rice together into clumps. I stir, trying to incorporate enough of the ambient cold to bring the koji down to a reasonable temperature in the low hundreds. "Alex," I say, "You are not going to believe this."

The tricky part, as it turns out, is keeping it cool.

In The Book of Miso William Shurtleff describes Koji Rooms inhistorical miso factories. These are large rooms where the floor is covered in several inches of inoculated rice. In order to prevent the koji from overheating and burning itself out, the koji technicians would don special sandals, with long, skinny dowels covering the soles, creating a rake. They would then skate through the koji, aerating it and breaking up any clumps that may have formed. It is said that those rooms got warm enough that shafts were built from the koji rooms to the rest of the factory in order to heat it through the long winter months.

Our first couple of batches of koji were used for making shiro or sweet white miso, and a sweet, thick rice drink called amazake. Sweet white miso is a young, very quick-fermenting miso. The mashed soybeans are added to a small amount of salt and a large amount of koji. Salt—the great preserver—staved off rot, giving the chosen mold the opportunity to transform. Alchemy. The result is a miso that comes of age in only a few weeks, yielding a paste that is sweet and mild enough to spread thickly on toast, an unthinkable act using the older and much more salty misos. Amazake, in turn, is made by combining koji with well-cooked sticky brown rice and water, letting it ferment for a number of hours, and allowing the starches in the rice to convert to sugars, after which you boil the mixture to halt fermentation and blend it into a sweet rice shake.

However, we are going to use this koji to make pickles.

-Kevin